Phylogenetic analysis of Oropouche virus

Miguel Paredes, James Hadfield, John SJ Anderson, Jover Lee, Trevor Bedford

We are pleased to announce the availability of an Oropouche phylogenetic analysis and dataset on Nextstrain.org, which is possible thanks to the rapid public sharing of sequences and metadata. Below describes an overview of Oropouche virus and a description of the phylogenetic analysis. We welcome feedback from Oropouche researchers about any aspects of this analysis and dataset.

# Phylogenetic analysis

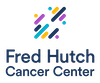

Oropouche virus is a segmented, negative-sense, single-stranded RNA virus from the Orthobunyavirus genus. It is the causative agent of Oropouche fever: an often self-limited, non-specific disease characterized by headache, arthralgia, myalgia, nausea, vomiting, chills, and/or photophobia. Oropouche virus is maintained primarily through an enzootic cycle between pale-throated sloths (Bradypus tridactylus), non-human primates and other wild mammals via transmission through Culicoides paraensis midges, with urbanization contributing to the rise of human cases acquired through the same arthropod vector (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Time-resolved phylogeny for the L segment colored by the host the sample was acquired from. 98% of sequences in our sample are human, so we have very limited information into the host reservoir dynamics. Available as nextstrain.org/oropouche/L?c=host.

Figure 1. Time-resolved phylogeny for the L segment colored by the host the sample was acquired from. 98% of sequences in our sample are human, so we have very limited information into the host reservoir dynamics. Available as nextstrain.org/oropouche/L?c=host.

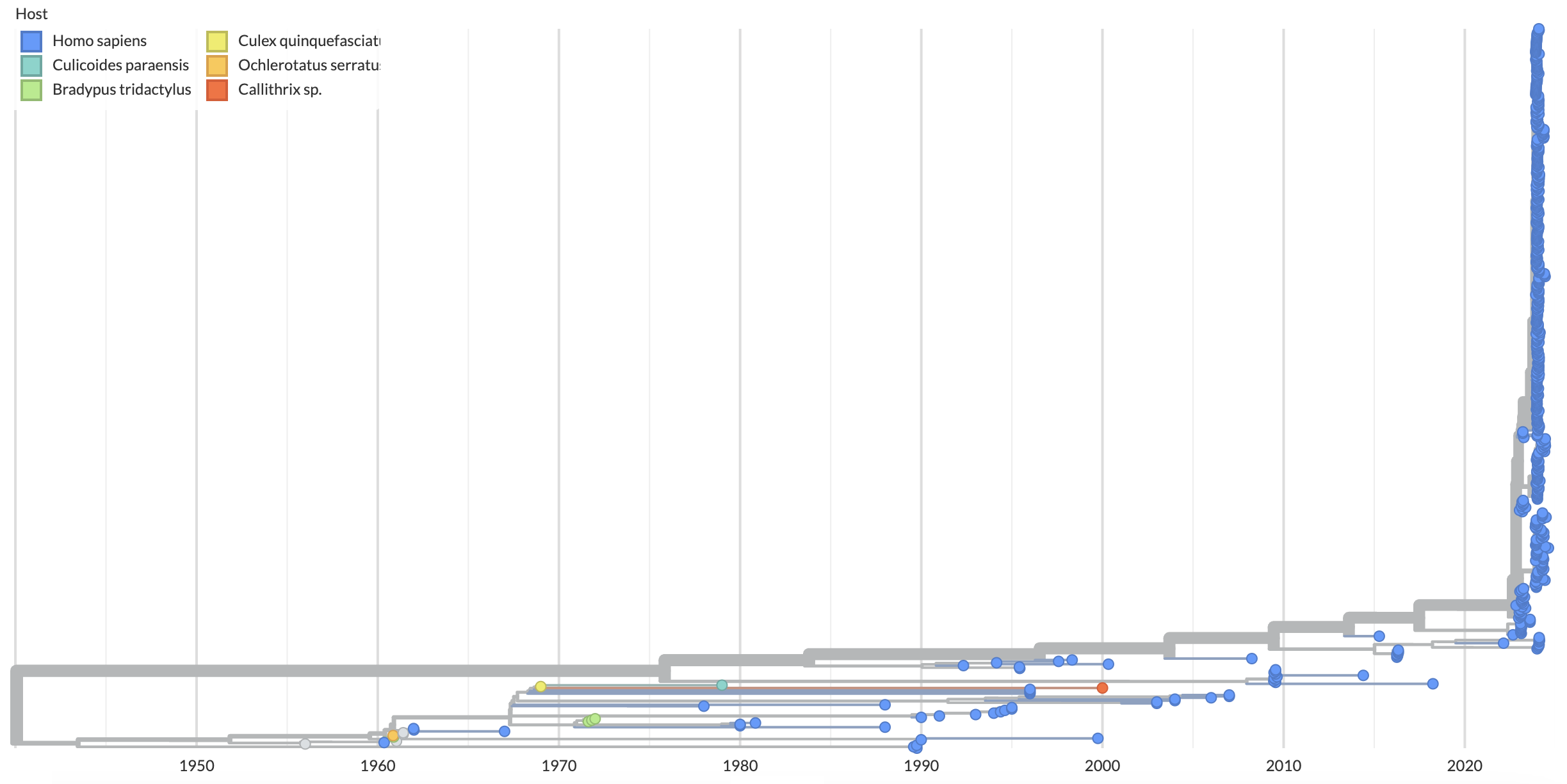

Since its original description in 1955 in Trinidad and Tobago, Oropouche virus has caused multiple local outbreaks throughout Latin America, primarily in Amazonian states of Brazil (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Geographic spread of Oropouche virus in the Americas. Available as nextstrain.org/oropouche/L.

Figure 2. Geographic spread of Oropouche virus in the Americas. Available as nextstrain.org/oropouche/L.

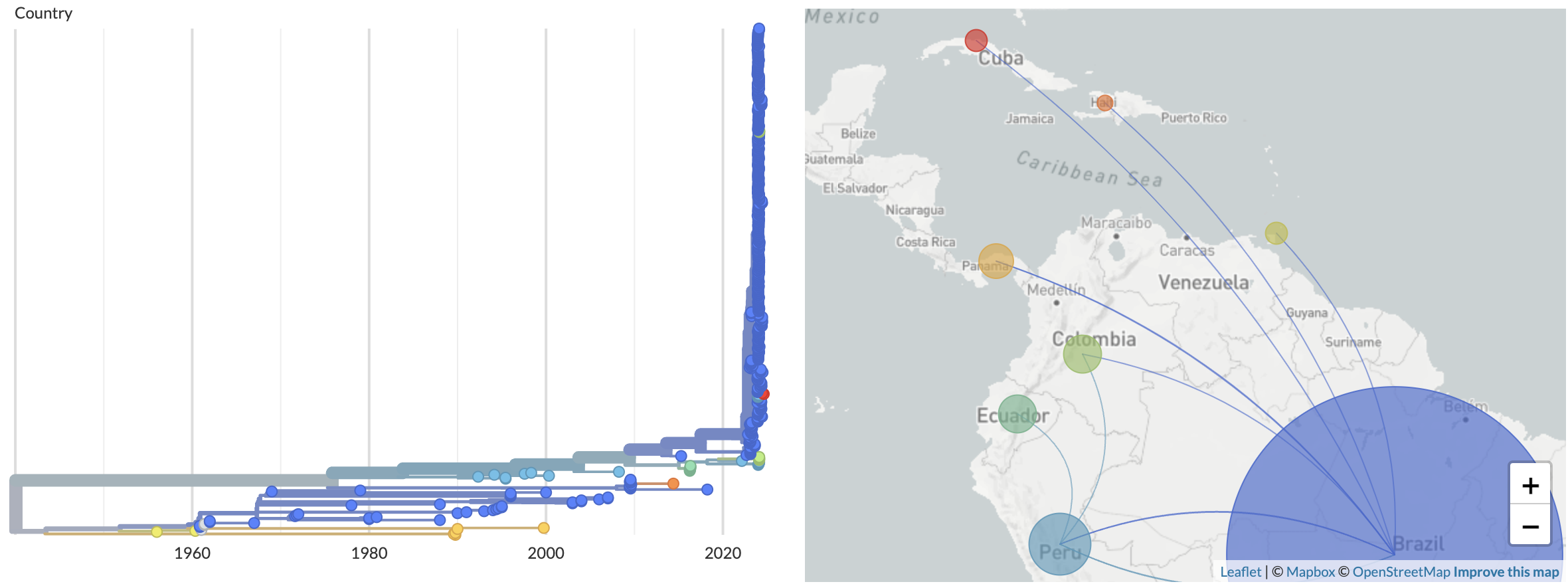

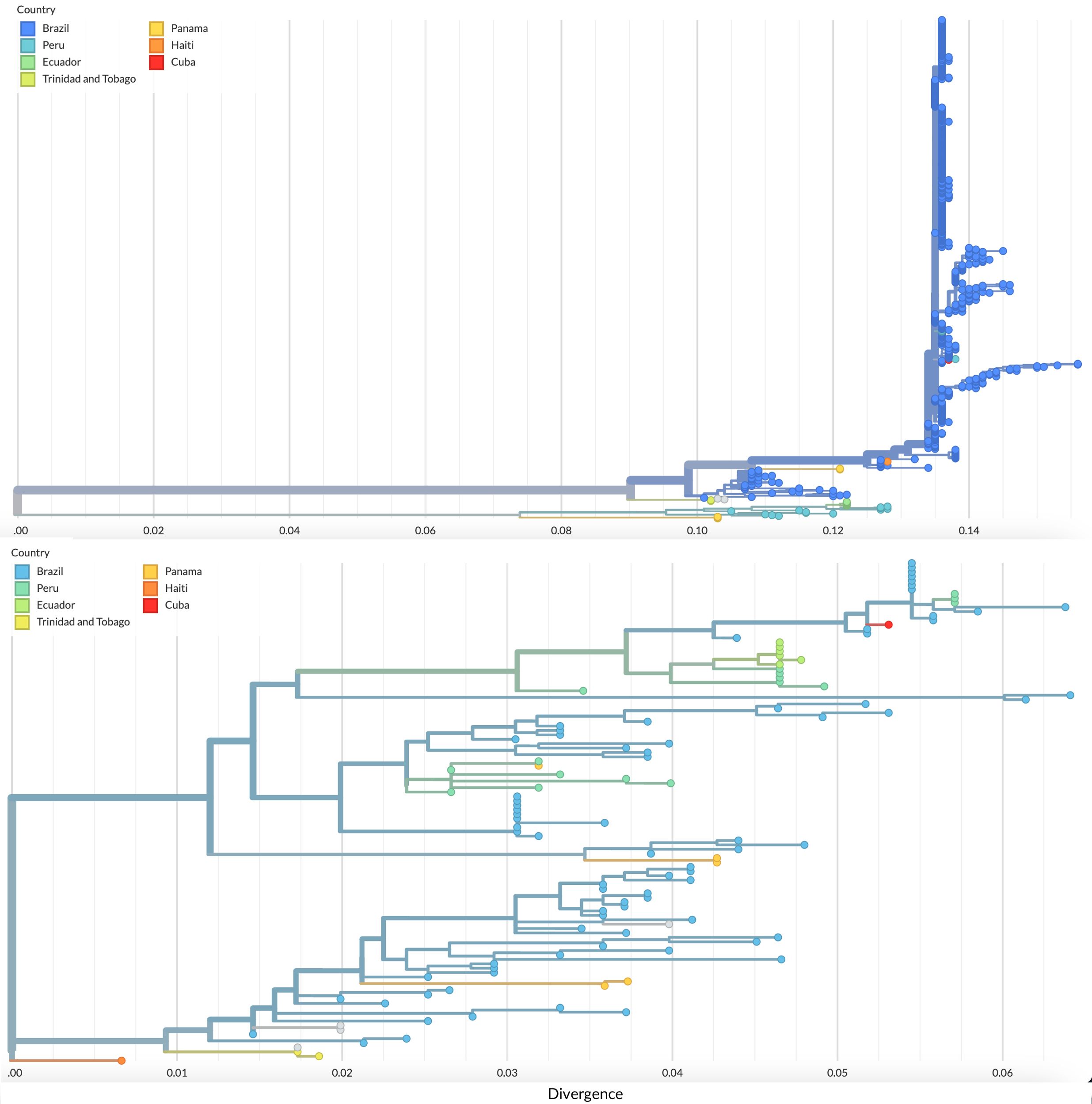

Since late 2023, however, there has been a documented increase in local cases not only in Brazil but also in Cuba, Bolivia, Colombia, Peru, as well as travel-associated cases not only throughout the Americas but in Europe as well. In 2024 alone, there have been more than 9,800 confirmed cases, including two deaths. We find the majority of cases in 2023-2024 nested within the diversity of the viruses sampled in Brazil, suggesting Brazil as a main source (Fig. 3). Alternatively, we also see evidence of a separate, ongoing lineage in Peru.

Figure 3. L segment tree shows the 2023-2024 sequences from Brazil clustering together. Sequences from Cuba, Colombia and Ecuador nest within the diversity of this Brazilian clade. Concurrently, we also see an ongoing lineage in Peru that is separate from the Brazilian clade. Available as nextstrain.org/oropouche/L.

Figure 3. L segment tree shows the 2023-2024 sequences from Brazil clustering together. Sequences from Cuba, Colombia and Ecuador nest within the diversity of this Brazilian clade. Concurrently, we also see an ongoing lineage in Peru that is separate from the Brazilian clade. Available as nextstrain.org/oropouche/L.

Oropouche virus has a segmented genome made up of the L (Large), M (Medium), and S (Small) segments; phylogenetic trees for these segments are constructed independently:

- https://nextstrain.org/oropouche/L

- https://nextstrain.org/oropouche/M

- https://nextstrain.org/oropouche/S

The segmented nature of Oropouche virus allows for genetic reassortment events. Similarly to Gutierrez et al., all three phylogenies display topographical differences, suggesting the presence of reassortment events on the genome. For example, while the phylogenies of the L and M segments show more robust clustering of the sequences from Brazil throughout time, the S segment phylogeny shows the Brazil sequences scattered throughout the tree (Fig. 4). If we focus on the most recent sequences from 2022-2024, however, we do find more robust clustering of the sequences from Brazil, similar to the results presented by Naveca et al.

Figure 4. Comparison of the M (top) and S (bottom) segment trees shows distinct topographical differences, suggesting the presence of reassortment events. Available as nextstrain.org/oropouche/M and nextstrain.org/oropouche/S respectively.

Figure 4. Comparison of the M (top) and S (bottom) segment trees shows distinct topographical differences, suggesting the presence of reassortment events. Available as nextstrain.org/oropouche/M and nextstrain.org/oropouche/S respectively.

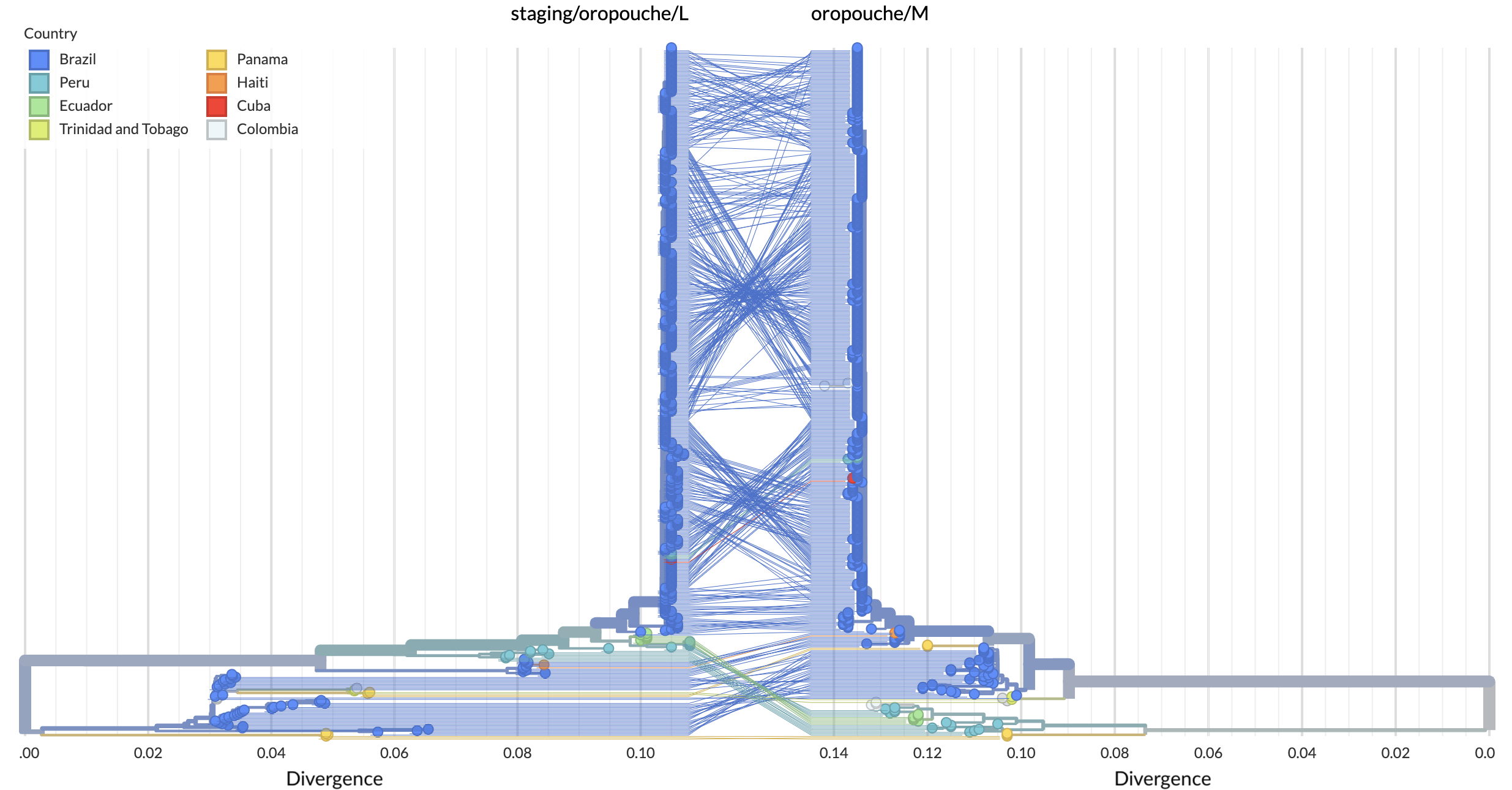

We can track the co-evolution of the Oropouche segments via tanglegrams. For example, if we focus on the L and M segments (Fig. 5), we can see evidence of at least two recombination events.

Figure 5. Tanglegram of L and M segments. Available as nextstrain.org/oropouche/L:oropouche/M.

Figure 5. Tanglegram of L and M segments. Available as nextstrain.org/oropouche/L:oropouche/M.

# Nextstrain resources

# Curated sequences and metadata

We curate sequence data and metadata from NCBI as the starting point for our analyses. Curated sequences and metadata are available as flat files at:

- data.nextstrain.org/files/workflows/oropouche/metadata.tsv.zst

- data.nextstrain.org/files/workflows/oropouche/L/sequences.fasta.zst

- data.nextstrain.org/files/workflows/oropouche/M/sequences.fasta.zst

- data.nextstrain.org/files/workflows/oropouche/S/sequences.fasta.zst

# Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the authors, originating and submitting laboratories of the genetic sequences and metadata for sharing their work. Many of the recent sequences come from various publications and preprints, such as Naveca et al., Scachetti et al., Iani et al., among others.