New Resources for Rabies, Lassa, and Yellow Fever Virus

Kim Andrews, Jennifer Chang, Richard Daodu, Denise Kühnert, John SJ Anderson

We are continuing to expand the collection of core pathogen datasets in Nextstrain that are automatically updated. We now provide regularly updated phylogenetic monitoring of rabies, Lassa fever, and yellow fever virus at:

These phylogenies are generated using genomic data from NCBI GenBank, and are updated daily when new sequences are uploaded to NCBI.

# Rabies

Rabies lyssavirus (RABV) causes rabies, a disease that affects the central nervous system and is fatal if not treated before symptoms start. Globally, rabies causes more than 60,000 human deaths annually, primarily in Asia and Africa. All mammalian species can be infected by RABV, and the virus is transmitted through bites and scratches from infected animals. The most common source of human infections is transmission from domestic dogs, although some countries have essentially eliminated dog-to-human transmission as a result of wide-scale dog vaccination. Person-to-person transmission is very rare for this virus.

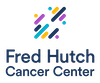

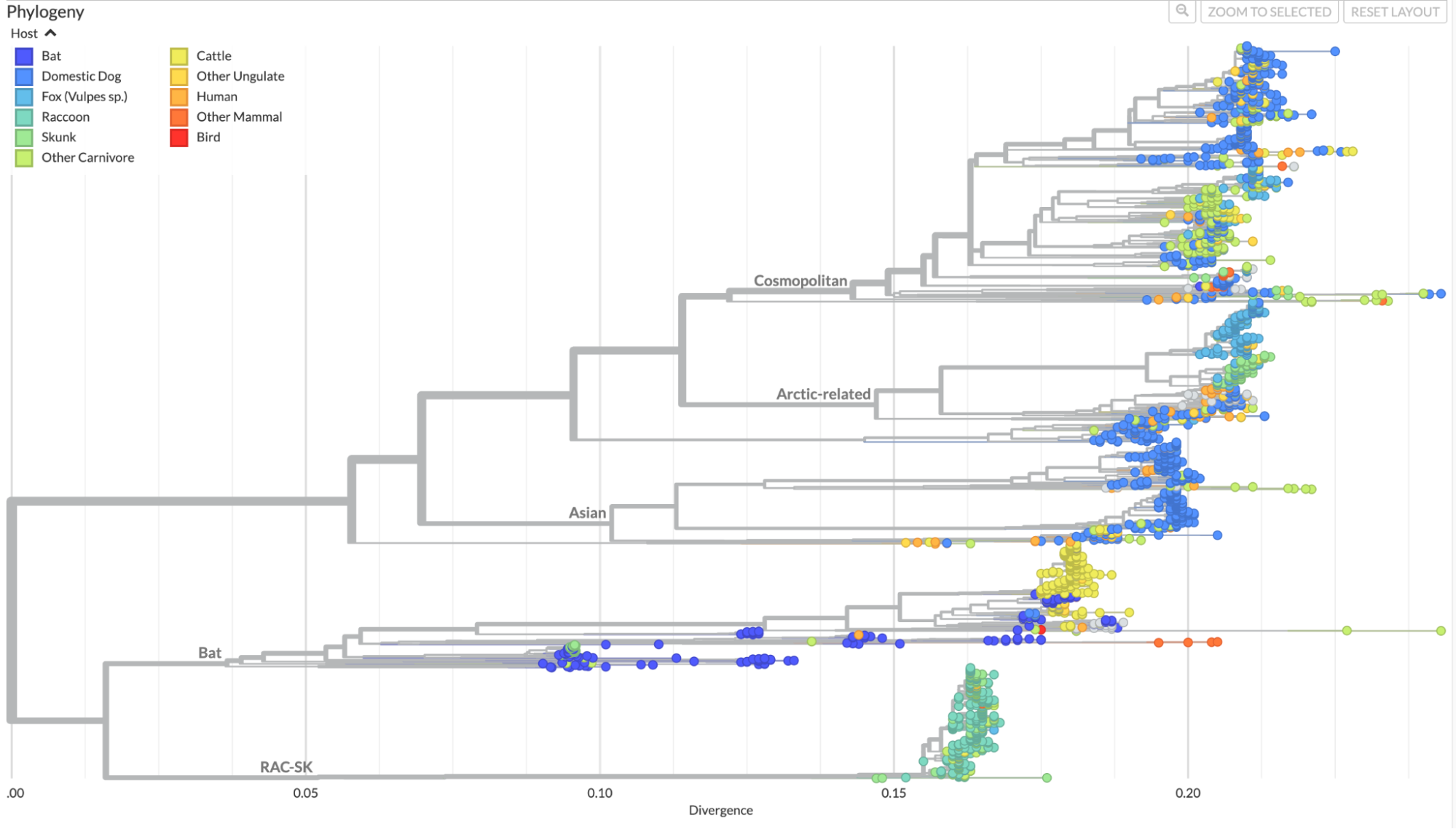

Our analysis includes a full genome phylogeny, and provides coloring of host species based on taxonomic groups that play the most prominent roles in the transmission of this pathogen (Fig. 1). The phylogeny also shows clade assignments for each sequence based on the "major clades" defined in Troupin et al. 2016. By default, these clade assignments are viewed as branch labels, and they can also be viewed as coloring of branches and tips by choosing the option to color by “Clade.” We do not provide a time-resolved phylogeny for RABV, because this pathogen does not demonstrate a consistent clock rate across the phylogeny, likely due to variation in evolutionary rates for the virus across host species.

Figure 1. Phylogenetic tree of rabies viruses from across the globe

and from a wide variety of host species alongside a map showing

distribution of these samples. The phylogenetic tree and map are

colored by host species, and branches in the tree are labeled based on

major clades defined in Troupin et al. 2016. Available at

nextstrain.org/rabies.

Figure 1. Phylogenetic tree of rabies viruses from across the globe

and from a wide variety of host species alongside a map showing

distribution of these samples. The phylogenetic tree and map are

colored by host species, and branches in the tree are labeled based on

major clades defined in Troupin et al. 2016. Available at

nextstrain.org/rabies.

# Lassa fever

Lassa fever is a haemorrhagic disease endemic in West Africa. The causative virus (Lassa mammarenavirus, LASV) is usually spread by the mouse Mastomys natalensis and other reservoir host rodents (Olayemi et al. 2015; Happi et al. 2022; Gary, 2023) and person-to-person transmission is rare. Outbreaks of Lassa tend to occur from December to March (llori et al, 2019, McKendrick et al, 2023). The Lassa virus genome is composed of two segments — a ~7k nucleotide L segment and a shorter ~3k nucleotide S segment. The S segment encodes the ~490 (largely 491 for lineage 4 and 5 and 490 for lineages 1,2,3; Daodu et al, preprint, figure 2) amino acid Glycoprotein Complex (GPC) which is the surface protein and the main target for neutralizing antibodies.

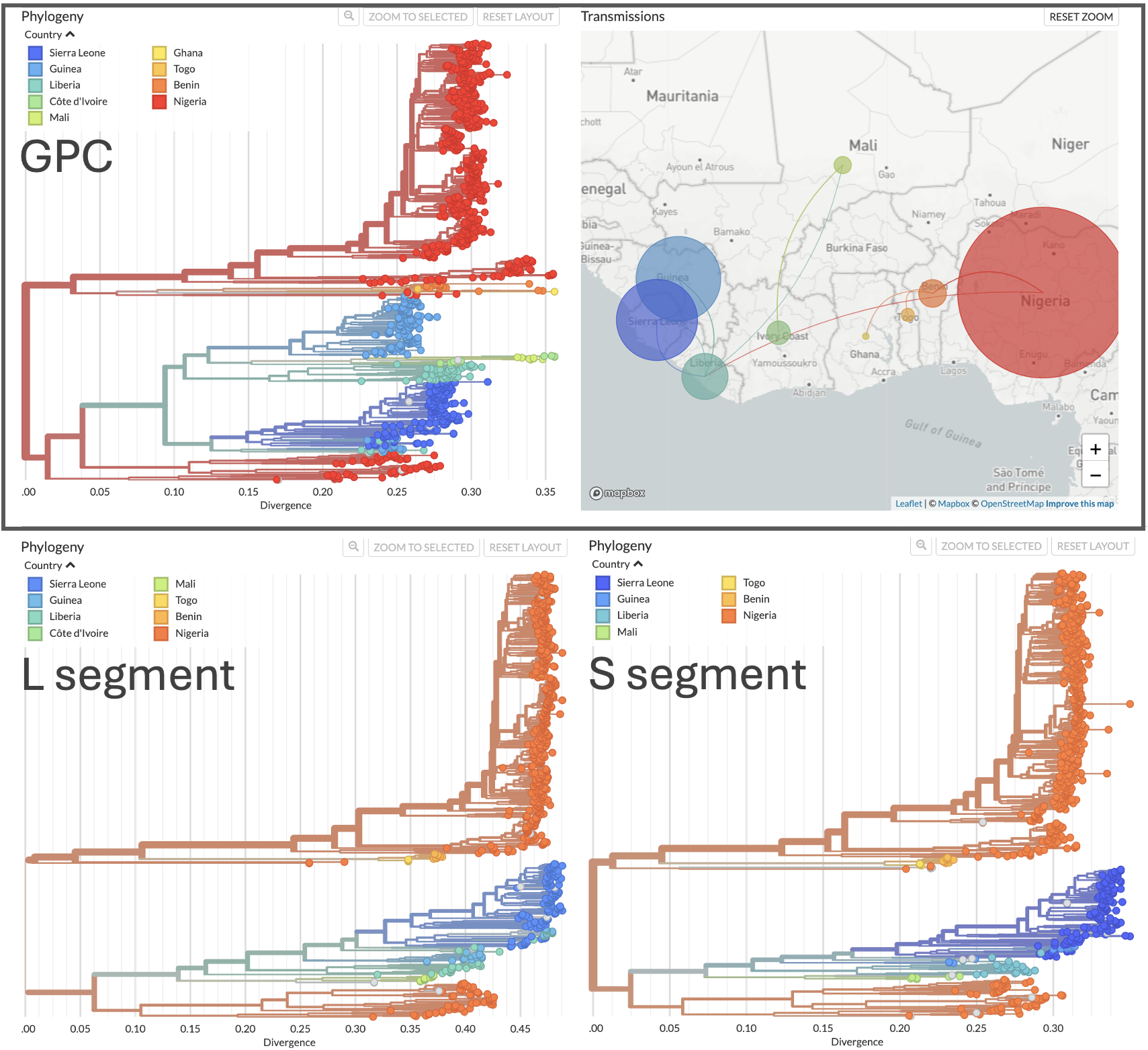

Nextstrain phylogenetic trees by segment were built against the Josiah

strain (GenBank reference NC_004297 for L segment; NC_004296 for S

segment) and mid point rooted. This enables the

visualization of the global distribution of Lassa virus across its

segments – which is geographically constrained across lineages

(Ehichioya et al. 2019). Hence, the introduction of lineages (or

strains) to new locations can be promptly detected.

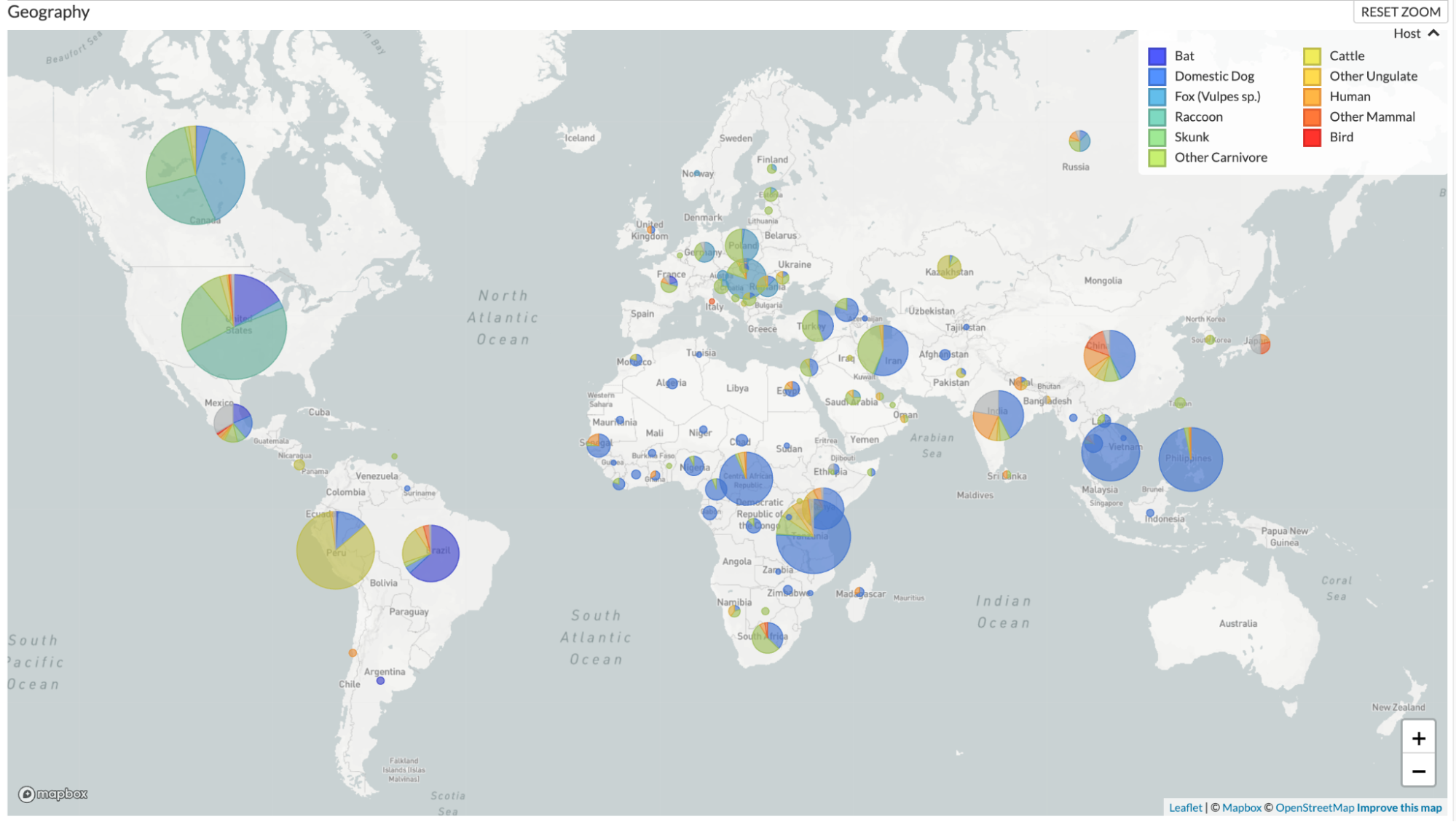

A manually cleaned GPC alignment was used to enable a more codon

aware alignment for the GPC phylogenetic tree (Figure 2 green boxes).

New sequences are matched against this guide alignment (used by

mafft --extend-alignment) which enables tracking of a commonly observed

position 60 indel region in the GPC (Perrett et al. 2023 figure S1,

Buck et al., 2022 Fig S4). This region is also a key position

implicated in a study that applied machine learning analysis to LASV

GPC sequences for lineage assignment, suggesting that this indel is

more prevalent than previously thought (Daodu et al, preprint, figure

2). Similar codon-aware guide alignments for the S and L regions are

in development. Further feedback from other Lassa researchers is

welcome.

Figure 2. Manual alignment vs. Nextclade alignment. An indel region

within the GPC pos 60 region resulted in challenging codon alignment

for Augur Align (mafft) and Nextclade alignment (despite increasing

the penalty-gap-open-out-of-frame). The manual fix adjusted the

alignment results to maintain the indel in-frame. For example, the GPC

pos 60 region for GenBank OR147792 (highlighted in pink) was manually

fixed (highlighted in green). The Josiah strain (NC004296)

is shown at the top for reference.

Figure 2. Manual alignment vs. Nextclade alignment. An indel region

within the GPC pos 60 region resulted in challenging codon alignment

for Augur Align (mafft) and Nextclade alignment (despite increasing

the penalty-gap-open-out-of-frame). The manual fix adjusted the

alignment results to maintain the indel in-frame. For example, the GPC

pos 60 region for GenBank OR147792 (highlighted in pink) was manually

fixed (highlighted in green). The Josiah strain (NC004296)

is shown at the top for reference.

Host and geographic information were annotated onto the different phylogenies. The host tip colors have been manually ordered from Human to M. natalensis to better emphasize host switching. As expected, sequences from humans are more prevalent than from rodents in the tree, reflecting greater sequencing effort for human cases. Among rodent samples, more sequences are available from the GPC and S than the L region. Additionally, geographic information was manually adjusted for one case in Germany, which originated from traveling in the West Africa region. Apart from this exported case, the phylogeography is consistent with Lassa virus being endemic to West Africa.

Figure 3. Phylogenetic trees of Lassa virus GPC gene and segments.

The phylogenetic trees are colored by country of collection.

Phylogenies and more detailed views available at nextstrain/lassa/gpc,

nextstrain/lassa/l, and nextstrain/lassa/s respectively.

Figure 3. Phylogenetic trees of Lassa virus GPC gene and segments.

The phylogenetic trees are colored by country of collection.

Phylogenies and more detailed views available at nextstrain/lassa/gpc,

nextstrain/lassa/l, and nextstrain/lassa/s respectively.

# Yellow fever

Yellow fever is a mosquito-borne viral disease. It is generally a short-lived infection, but in a minority of cases can cause severe liver damage and even death. The jaundice from the liver damage gives the disease its name. Yellow fever is caused by the yellow fever virus (Orthoflavivirus flavi, YFV), a member of the single-stranded RNA Flaviviridae family. Despite the existence of a safe and highly effective vaccine, yellow fever remains an endemic disease in the tropical regions of Africa and South America, and has been detected in most regions of the world.

Like many arboviruses, yellow fever circulates in one of three infectious cycles: a “sylvatic” or forest cycle, a “savannah” or intermediate cycle, and an “urban” cycle, which drives epidemics in human populations. Interestingly, the mosquito host species is distinct in each type of cycle, with the “urban” cycle depending on Aedes aegypti, which is also an important host for Zika and dengue viruses, which are also in the Flaviviridae family.

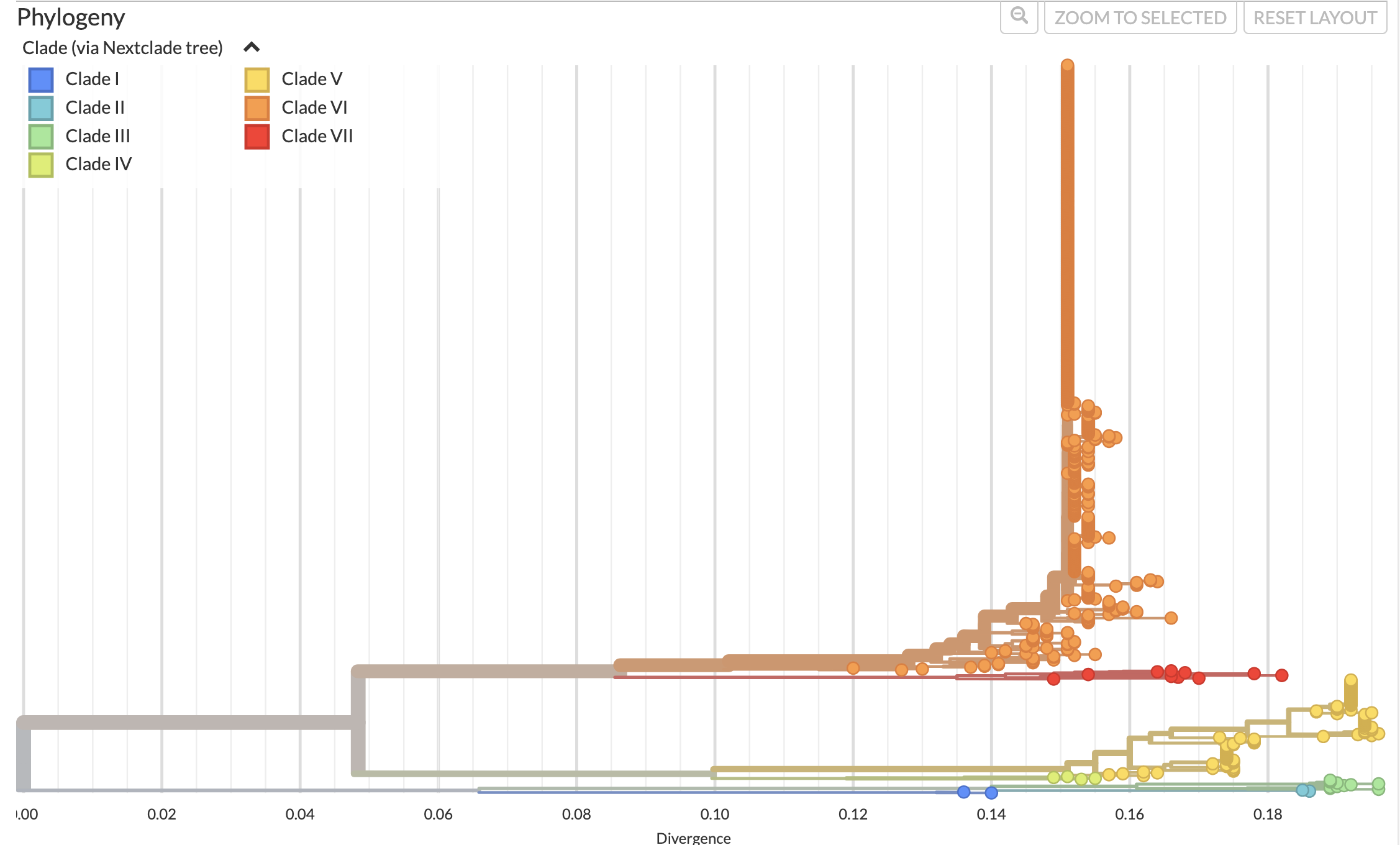

Our Nextstrain yellow fever dataset makes use of a Nextclade dataset in order to assign strains to different clades. This Nextclade dataset is based on data from Mutebi et al. 2001 and Bryant et al. 2007, with the assigned clades mapping to the genotypes in those two papers as follows:

| Clade | Genotype |

|---|---|

| Clade I | Angola |

| Clade II | East Africa |

| Clade III | East/Central Africa |

| Clade IV | West Africa I |

| Clade V | West Africa II |

| Clade VI | South America I |

| Clade VII | South America II |

(This table is available as a TSV file in the yellow fever GitHub repo.)

The Nextstrain yellow fever dataset contains two phylogenies: one for whole genome sequences, and a second specific to the “prM-E” region of the genome. That region was chosen because historically, it has been a frequent sequencing target, and is the genome region that was used to develop the Nextclade dataset linked above. As new yellow fever virus sequences are deposited into GenBank, the Nextstrain phylogenies will be automatically updated.

Figure 4. Phylogenetic tree of yellow fever virus prM-E region.

The phylogenetic tree is colored by clade assignment, based on clades

defined in Mutebi et al. 2001 and Bryant et al. 2007. Available at

nextstrain.org/yellow-fever.

Figure 4. Phylogenetic tree of yellow fever virus prM-E region.

The phylogenetic tree is colored by clade assignment, based on clades

defined in Mutebi et al. 2001 and Bryant et al. 2007. Available at

nextstrain.org/yellow-fever.

# Please contribute!

We welcome comments or suggestions from rabies, Lassa, and yellow fever researchers to improve these Nextstrain datasets for their use case. Special thanks for feedback from Laura McMullen for answering questions and providing some biological context.