Phylogenetic analysis of H5N1 cattle outbreak and curated genomic data

Trevor Bedford, Jover Lee, James Hadfield, John Huddleston, Louise Moncla

# Phylogenetic analysis

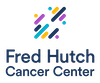

The 2.3.4.4b clade of influenza subtype H5N1 has been remarkably successful in its global spread with arrival into Europe in mid-2020, into North America in late 2021 and into South America in mid-2022 (Fig. 1). Although sustained transmission and spread has been largely within birds, these viruses have infected a number of species of non-human mammals, including foxes, skunks and domestic cats which appear to be dead-end hosts to infection, but also seals in North America and sea lions in South America, where sustained transmission outside of birds is highly likely.

Figure 1. Broader context of H5N1 evolution and spread.

Available as nextstrain.org/avian-flu/h5n1/ha/all-time.

Figure 1. Broader context of H5N1 evolution and spread.

Available as nextstrain.org/avian-flu/h5n1/ha/all-time.

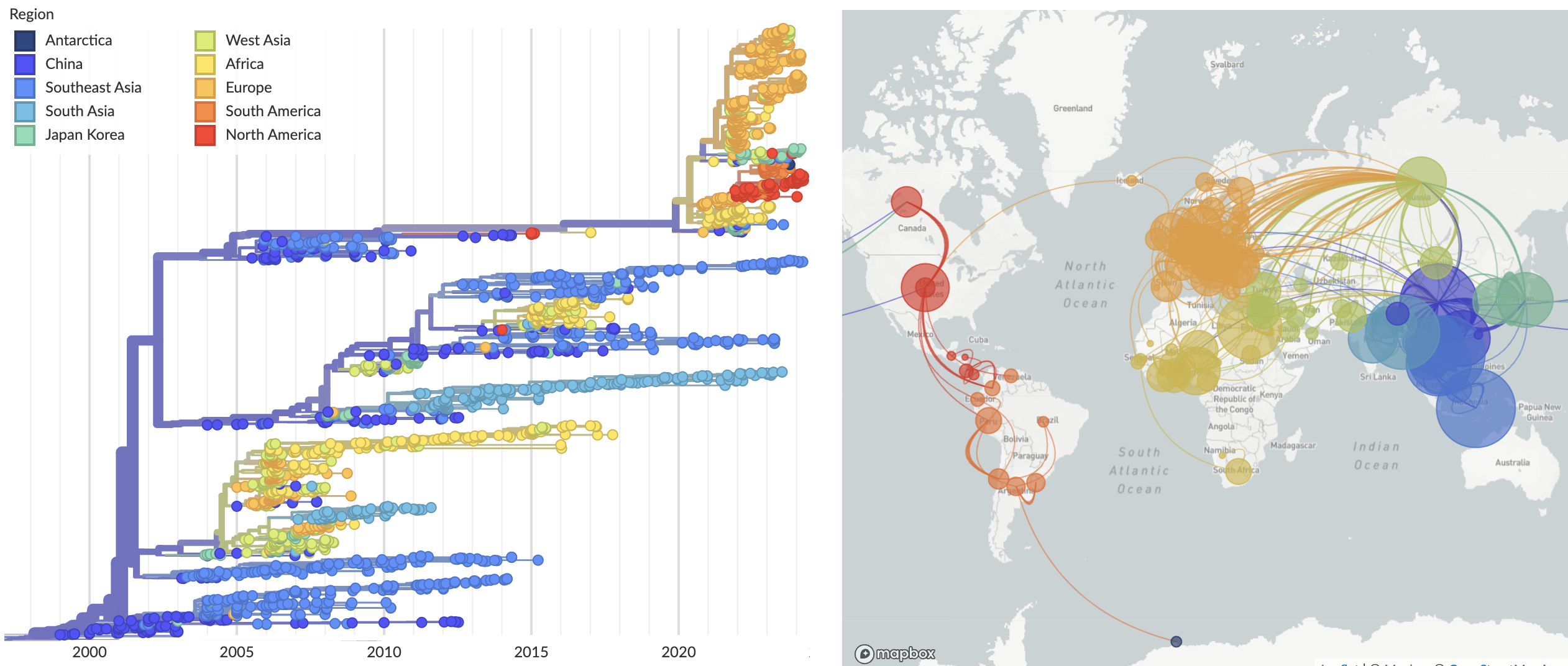

More recently, this clade of H5N1 was discovered circulating in dairy cows in the US with cases first reported in Texas in March 25, 2024. Consensus genomes from infected dairy cattle have been shared to GenBank primarily by the National Veterinary Services Laboratories (NVSL) of the Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) of the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). We find, in accordance to results by Nguyen et al and by Worobey et al, that cattle-associated viruses form a distinct monophyletic clade across all 8 segments (Fig. 2). Comparing phylogenetic structure across segments shows reassortment in birds prior to cattle spillover, but that the cattle clade appears to be non-reassorting.

Figure 2. Cattle infections form a distinct clade across segments indicative of single spillover and cow-to-cow spread.

Segment-level trees available for HA, PB2, PA, etc...

Figure 2. Cattle infections form a distinct clade across segments indicative of single spillover and cow-to-cow spread.

Segment-level trees available for HA, PB2, PA, etc...

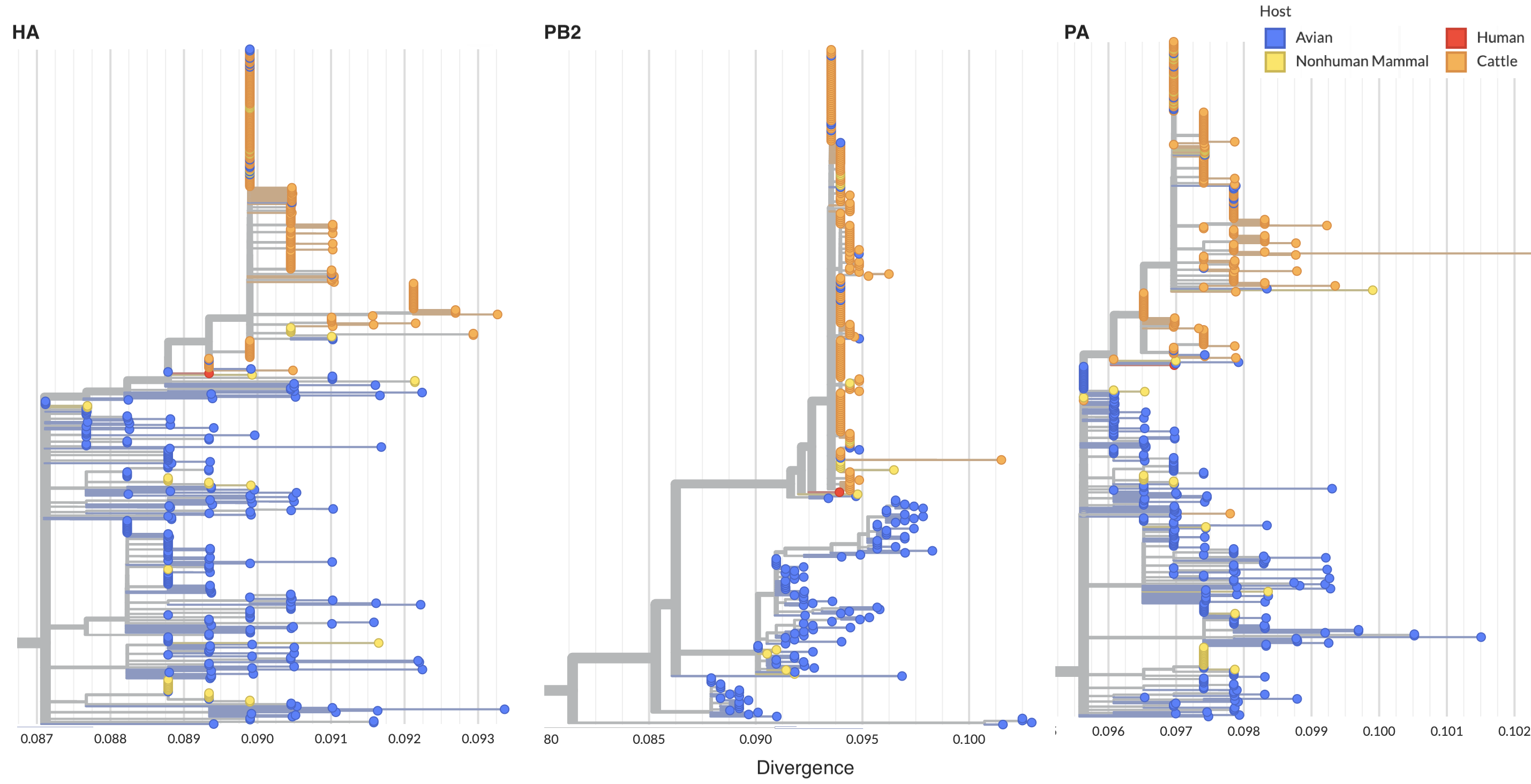

Consequently, we have constructed a full genome phylogenetic analysis at nextstrain.org/avian-flu/h5n1-cattle-outbreak/ showing evolution and spread in cattle (Fig. 3). This treats concatenated segments as a standard full genome analysis by using a synthetic reference sequence and gene coordinates on this reference sequence. The resulting tree has significantly more phylogenetic resolution than single genome trees. This difference can be seen in the reduced number of polytomies (identical sequences) in the full genome analysis compared to single segment analyses. With increased phylogenetic resolution, we observe evidence for clock signal within the cattle outbreak clade. Stronger clock signal and greater phylogenetic resolution allow for more fine-grained estimates of spatiotemporal patterns than available from single segments.

Figure 3. Full genome analysis of concatenated segments provides substantially finer resolution.

Available as nextstrain.org/avian-flu/h5n1-cattle-outbreak/genome?m=div.

Figure 3. Full genome analysis of concatenated segments provides substantially finer resolution.

Available as nextstrain.org/avian-flu/h5n1-cattle-outbreak/genome?m=div.

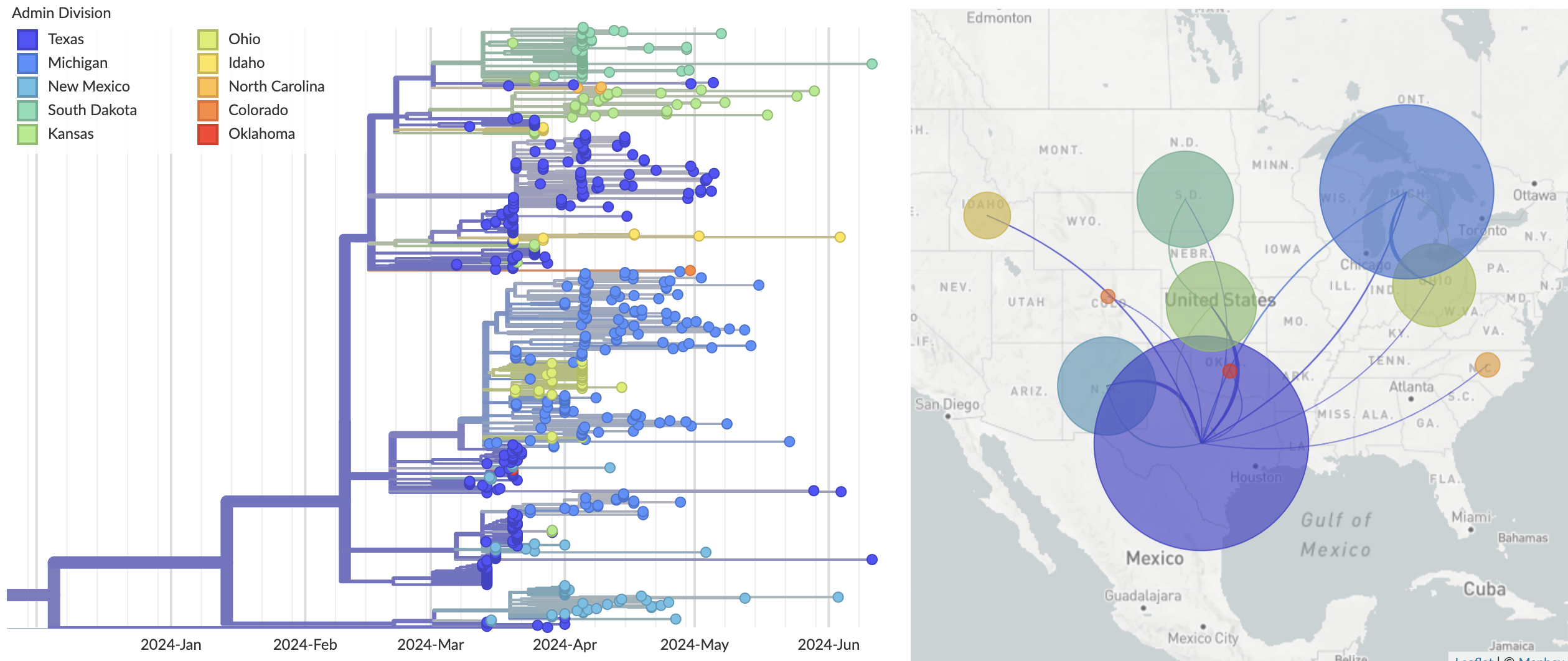

We estimate the common ancestor of sampled cattle sequences to be early February 2024 with a 95% confidence interval of late Nov 2023 to late Feb 2024. Additionally, we estimate this common ancestor to exist in Texas congruent with initial cases (Fig. 4). However, Texas is more heavily sampled than other states with 52% (136 of 260) of viruses sampled from Texas. This sampling bias may result in over-confidence in the inferred Texas location for the common ancestor.

Figure 4. Epizootic origin appears to be Texas congruent with initial cases.

Available as nextstrain.org/avian-flu/h5n1-cattle-outbreak/genome?c=division.

Figure 4. Epizootic origin appears to be Texas congruent with initial cases.

Available as nextstrain.org/avian-flu/h5n1-cattle-outbreak/genome?c=division.

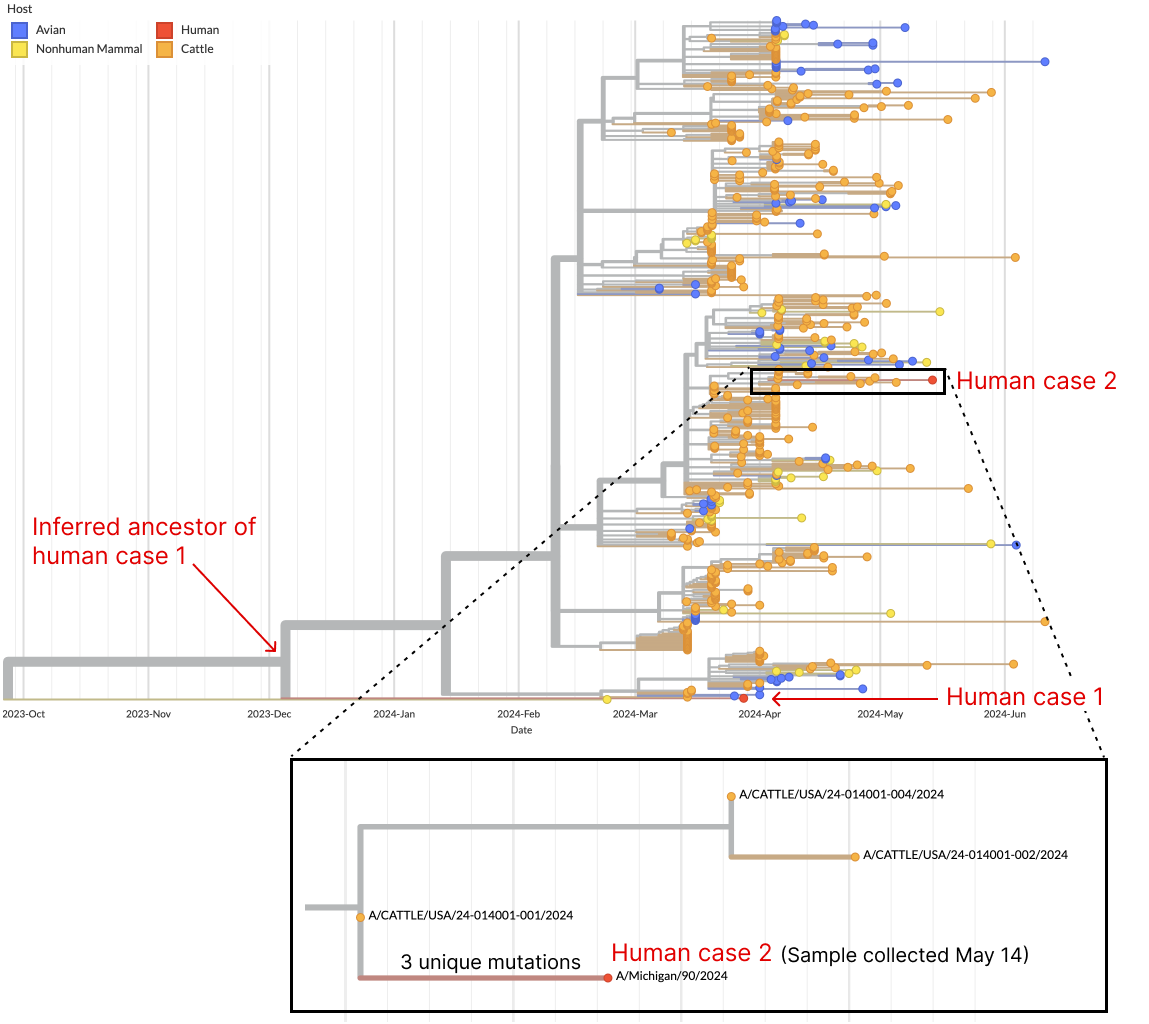

So far three human cases have been linked to this outbreak and we include genome sequences for two of these. The first case has no proximal sequenced viruses which perhaps indicates a gap in sampling around the cattle cases which led to this infection, while the second case, a worker on a dairy farm in Michigan, groups with cattle from Texas suggesting unsampled cattle-cattle transmission from Texas to Michigan which subsequently infected the worker (Fig. 5). Recently there was a fatal human case of H5N2 avian flu in Mexico however this is a different influenza subtype from the H5N1 viruses that are related to the cattle outbreak.

Figure 5. One human case nests outside of sequenced cattle diversity, while the other nests within.

Available as nextstrain.org/avian-flu/h5n1-cattle-outbreak/genome.

Figure 5. One human case nests outside of sequenced cattle diversity, while the other nests within.

Available as nextstrain.org/avian-flu/h5n1-cattle-outbreak/genome.

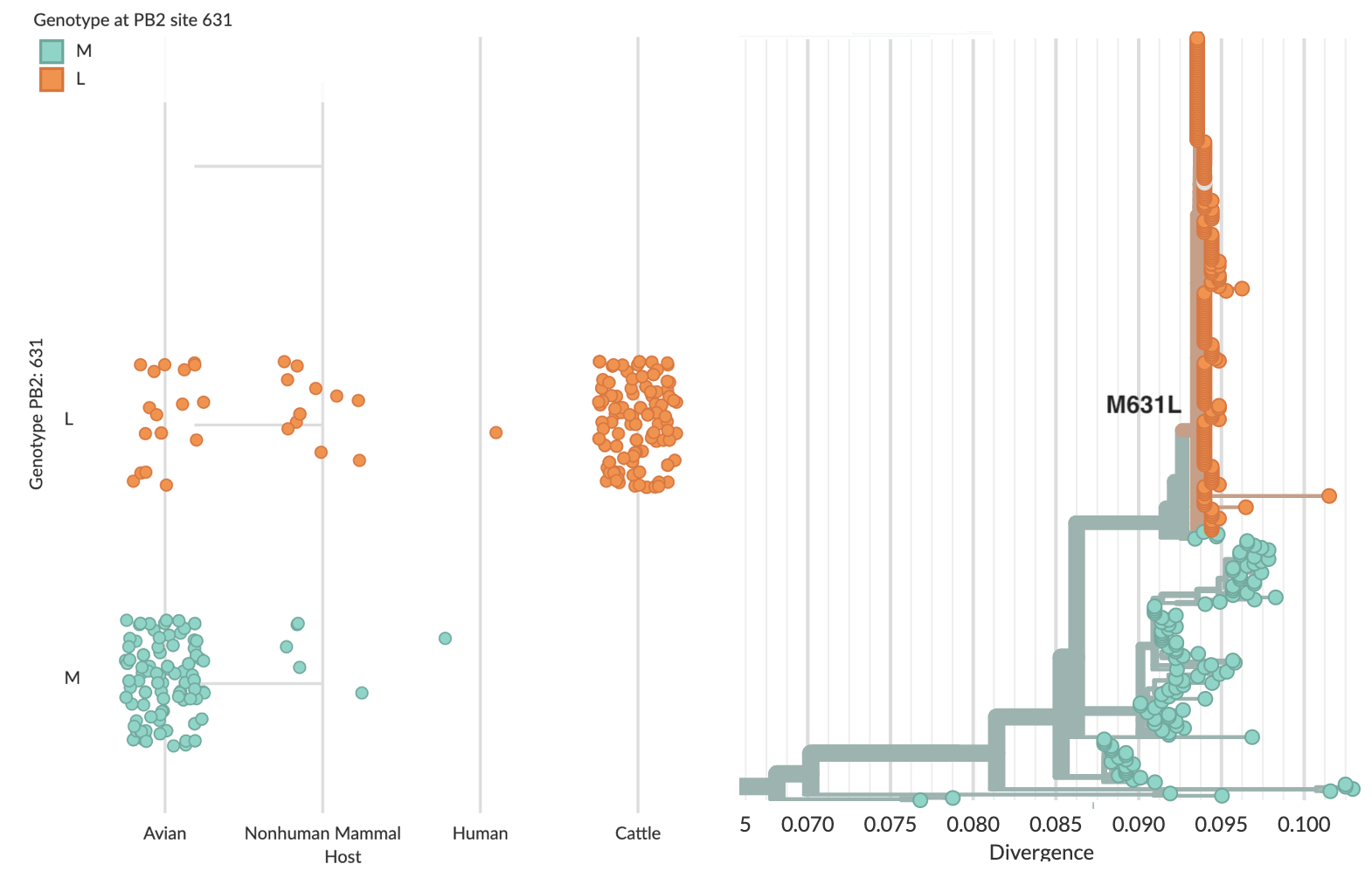

Specific mutations to the viral RNA polymerase are associated with the cattle outbreak, most obviously M631L in PB2 (Fig. 6), which may facilitate interaction with host protein ANP32 (Worobey et al). One-off human infections by H5N1 commonly evolved a similar mutation in PB2 E627K. Notably, the human case that outgroups to the cattle clade evolved E627K, while the human case that nests within the cattle clade did not, possibly because M631L is providing a similar benefit to the virus.

Figure 6. Association of PB2 mutation M631L with cattle infections.

Sequenced cattle-infecting viruses all possess PB2 mutation M631L.

Figure 6. Association of PB2 mutation M631L with cattle infections.

Sequenced cattle-infecting viruses all possess PB2 mutation M631L.

# Nextstrain resources

# Curated sequences and metadata

Currently, H5N1 sequence data is being shared to both NCBI GenBank and the SRA. We curate and merge sequence data from both sources.

We ingest consensus sequences shared to NCBI GenBank. During this curation process we:

- Merge data from NCBI Datasets and NCBI Virus as NCBI Datasets currently lacks "strain", "serotype" and "segment" entries as metadata

- Use strain name to match segments across separate GenBank entries into single viruses as GenBank treats each segment as an independent entity

- Scrape admin division from strain name, eg "Texas" from "A/cattle/Texas/24-009028-009/2024", as most GenBank records include location as /country="USA"

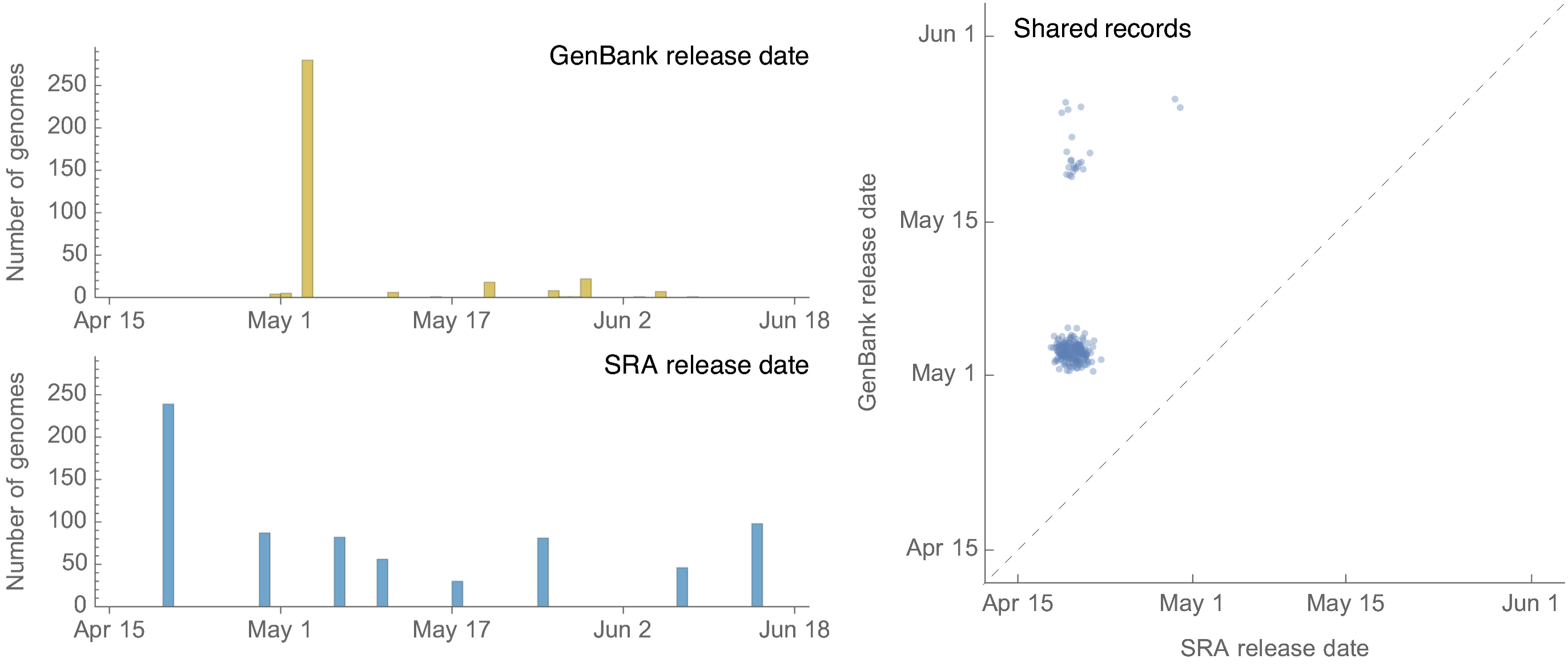

At the moment, USDA are first sharing raw sequence reads to SRA before sharing assembled consensus genomes to GenBank. Unfortunately these SRA entries lack metadata on time and place beyond “2024” and “USA”, which significantly impedes their utility for epizootic understanding. Additionally, the process of assembly is computationally intensive and it’s unwieldy for everyone analyzing these data to need to work from raw reads. This is a significant issue as, as of this writing, there are 293 consensus genomes from USDA available via GenBank, while there are 653 samples with sequencing reads in the SRA. Almost half the dataset is missing critical metadata and the most recently available consensus genomes were from samples collected in early April about two months ago.

To ameliorate this issue, Kartik Gangavarapu, Praneeth Gangavarapu and Kristian Andersen at Scripps have separately taken raw read data from the SRA, assembled it into consensus genomes and shared the resulting FASTA files via GitHub. During our ingest process, we merge these assembled consensus genomes with consensus genomes available via GenBank. We deduplicate between data sources based on SRA accession.

GenBank was updated with 280 genomes on May 3 by the USDA corresponding to data described in the Nyugen et al preprint, but following this there have been only 27 genomes shared to GenBank by the USDA since May 3 (Fig. 7). However, sharing to the SRA has continued with 393 submissions since May 3.

Figure 7. Release dates for H5N1 genomes from the US in GenBank and in the SRA.

Figure 7. Release dates for H5N1 genomes from the US in GenBank and in the SRA.

This ingest pipeline is run daily and resulting sequences files are available as:

- data.nextstrain.org/files/workflows/avian-flu/h5n1/ha/sequences.fasta.zst

- data.nextstrain.org/files/workflows/avian-flu/h5n1/na/sequences.fasta.zst

- data.nextstrain.org/files/workflows/avian-flu/h5n1/pb2/sequences.fasta.zst

- data.nextstrain.org/files/workflows/avian-flu/h5n1/pb1/sequences.fasta.zst

- data.nextstrain.org/files/workflows/avian-flu/h5n1/pa/sequences.fasta.zst

- data.nextstrain.org/files/workflows/avian-flu/h5n1/np/sequences.fasta.zst

- data.nextstrain.org/files/workflows/avian-flu/h5n1/ns/sequences.fasta.zst

- data.nextstrain.org/files/workflows/avian-flu/h5n1/mp/sequences.fasta.zst

and metadata available as:

# Phylogenetic workflows and live analyses

We provide phylogenetic workflows that analyze evolution at a few different scales. First of all, we provide a broad analysis of segment-level evolution of H5N1 viruses over the past >24 years at:

Notably, the currently circulating clade 2.3.4.4b viruses descend from the 2.3.4 clade of viruses that emerged around 2004 and began reassorting with other NA subtypes (primarily N2, N6, and N8), forming what are collectively referred to as H5Nx viruses. We also provide a complete evolutionary history of H5Nx since 1996 at:

These analyses are subsampled to target subsampling equitably across space and time and so many recent sequences are not included. To compensate for this, we provide a narrower analysis of segment-level of evolution of H5N1 and H5Nx viruses over the past 2 years at:

The targeted analysis of full genome evolution of the H5N1 cattle outbreak clade discussed above is available at:

# Nextclade placement of user data

While the panzootic in the Americas is caused by clade 2.3.4.4b viruses, endemic, low-path, "American non-GsGd lineage" H5Nx viruses have circulated endemically in the Americas for a half century. Other geographic regions harbor distinct viral clades (e.g., clade 2.3.2.1 descendants in Southeast Asia, and low-path Eurasian non-GsGd lineages in Europe) that can have distinct viral properties, making rapid clade assignment useful for surveillance. We released 3 Nextclade datasets that allow rapid, drag-and-drop assignment for circulating H5 clades: the 2.3.4.4 viruses and descendants, the 2.3.2.1 viruses and descendants, and all historic H5Nx clades. These datasets can be accessed at clades.nextstrain.org. These datasets provide clade assignments (including the recent 2.3.2.1 and 2.3.4.4 clade splits), quality control information, glycosylation site annotations, and information about the polybasic cleavage site. User-provided sequences will also be placed on a reference tree for visualization.

# Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the authors, originating and submitting laboratories of the genetic sequences and metadata for sharing their work. We thank the National Veterinary Services Laboratories (NVSL) of the Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) of the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) for open sharing of genomic data, along with other groups who have contributed. We thank the Andersen Lab for sharing assembled consensus genomes from SRA BioProject PRJNA1102327. We gratefully acknowledge the authors, originating and submitting laboratories of sequences from the GISAID EpiFlu Database on which this research is based.