Phylogenetic analysis of Human Metapneumovirus

Isabel Joia, Richard Neher

We are pleased to announce the availability of the hMPV phylogenetic analysis on Nextstrain and its corresponding Nextclade dataset. Below, we describe an overview of hMPV and its phylogeny. We welcome feedback from hMPV researchers about any aspects of this analysis and dataset.

# A Very Short History of hMPV

Human metapneumovirus is a globally circulating, airborne respiratory pathogen with a seasonal variance, peaking around the end of winter and during spring. While in healthy adults, hMPV typically causes a self-limited upper respiratory tract infection, certain groups are at risk of developing severe disease, such as immunocompromised patients, multimorbid patients and especially infants, causing bronchiolitis and, in serious cases, pneumonia. Clinically and epidemiologically, hMPV presents itself similarly to RSV. This is not surprising, given the close genetic relationship between the two viruses. Both are lipid-enveloped, non-segmented, negative-sense, single-stranded RNA viruses, classified within the Pneumoviridae family.

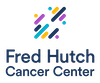

HMPV was first identified in the Netherlands in 2001, with its earliest sequence dating back to 1985. It is most closely related to avian metapneumovirus C. HMPV is postulated to have diverged from avian metapneumovirus between 200 and 400 years ago as a result of zoonotic transfer from birds. Since then, hMPV has evolved into two main clades, clade A and clade B, each further subdividing into distinct subclades (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Time resolved phylogeny for hMPV using full genome sequences. Clades A and B are estimated to have diverged from the most recent common ancestor around 1820. Their respective subclades A1, A2a, A2b1, A2b2, B1 and B2 are visualized in different colors.

Figure 1. Time resolved phylogeny for hMPV using full genome sequences. Clades A and B are estimated to have diverged from the most recent common ancestor around 1820. Their respective subclades A1, A2a, A2b1, A2b2, B1 and B2 are visualized in different colors.

# Sequencing Data

The hMPV genome consists of 8 different genes, the most commonly sequenced ones being gene F and gene G, which encode surface proteins, more specifically, the fusion protein and the glycoprotein. On nextstrain.org/hmpv we host the phylogenies of clades A and B based of the following sequences:

- Full genome

- Gene G

- Gene F

The phylogenies are generated using genomic data from NCBI GenBank, and are updated when new sequences are uploaded to NCBI. Currently, over 11,000 sequences are available, over 800 sequences for the entire genome, 1800 sequences for gene F and 3200 sequences for gene G. We curate sequence data and metadata from NCBI as the starting point for our analyses.

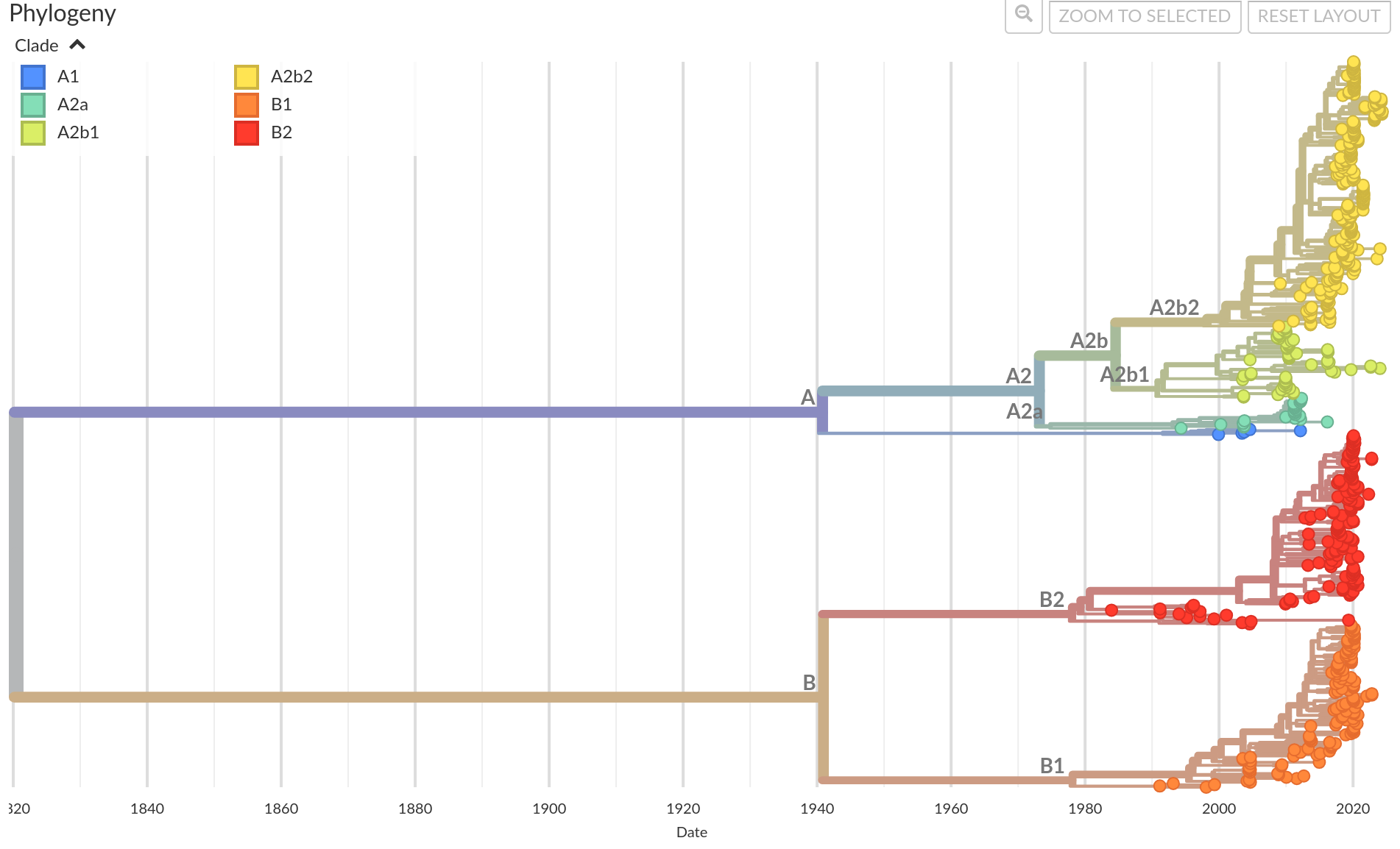

Figure 2. Global distribution and time resolved phylogeny of clade A using sequences from gene G. More extensive and representative phylogenies for gene G and gene F are possible, as more genetic data is available for these genes. Recently, we have seen a global increase in prevalence of clade A2b2 (in orange).

Figure 2. Global distribution and time resolved phylogeny of clade A using sequences from gene G. More extensive and representative phylogenies for gene G and gene F are possible, as more genetic data is available for these genes. Recently, we have seen a global increase in prevalence of clade A2b2 (in orange).

# Nextclade Dataset

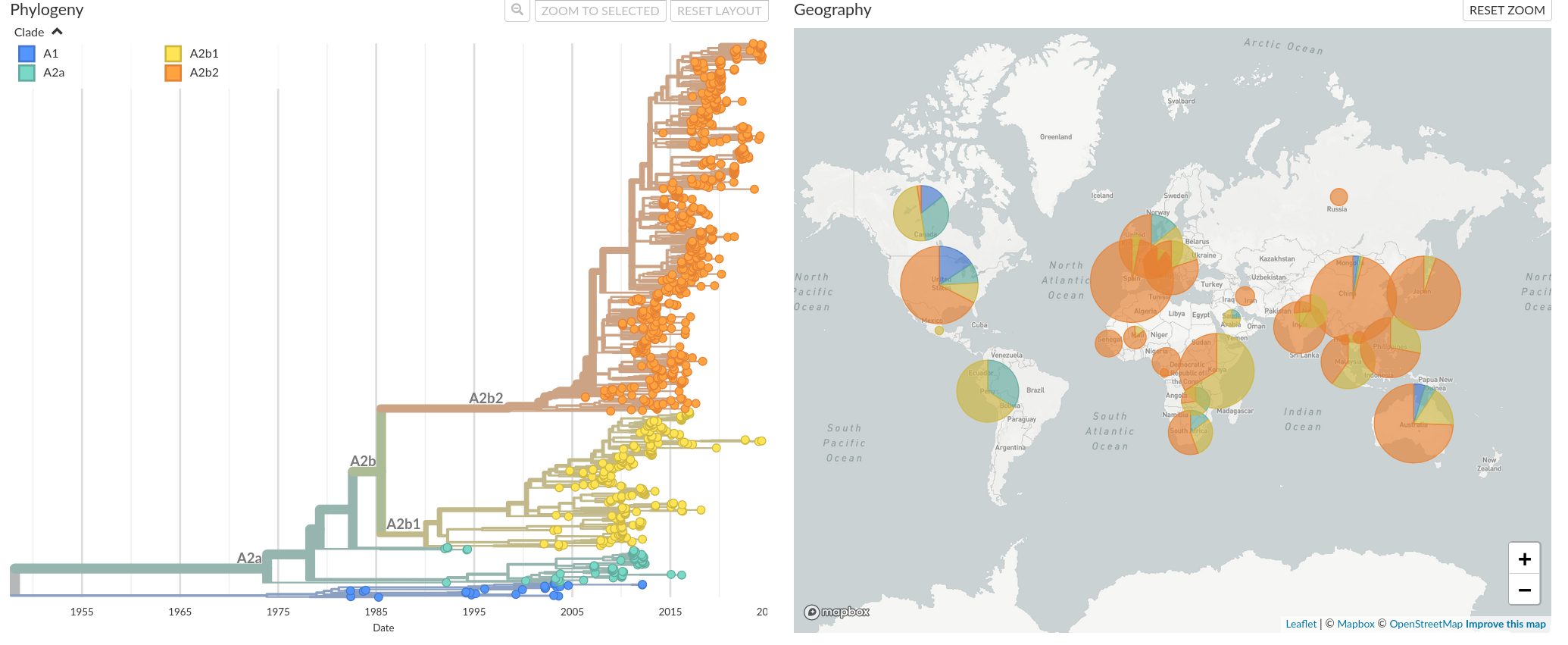

As part of this work, we developed an open-source tool for classifying hMPV genotypes. This tool is a Nextclade dataset, which allows users to drag-and-drop sequences onto a web browser to obtain the alignment to a hMPV reference genome from clade A. It also outputs quality control metrics, calls mutations, assigns clades and displays user sequences on the phylogenetic tree (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Example output for the hMPV Nextclade dataset. Each row contains the analysis for one sequence and includes (from left to right) the sequence name, quality control metrics, clade assignment, number of mutations, ambiguous nucleotides and missing nucleotides, coverage of the sequence, number of gaps, insertions, frame shifts, premature stop codons and finally, mutation placement.

Figure 3. Example output for the hMPV Nextclade dataset. Each row contains the analysis for one sequence and includes (from left to right) the sequence name, quality control metrics, clade assignment, number of mutations, ambiguous nucleotides and missing nucleotides, coverage of the sequence, number of gaps, insertions, frame shifts, premature stop codons and finally, mutation placement.

# Duplications in Gene G

While historically, clades A and B have annually circulated simultaneously to a similar extent, an increase in prevalence of A2b2 strains over the last few years has been observed. A common characteristic in these strains are up to 180 nucleotide long duplications in the G gene, which seem to have emerged around 2011. Interestingly enough, a similar evolution took place in RSV, where two independent duplications in the G gene occured and strains with these duplications quickly became the most dominant RSV subtypes. Both in RSV and hMPV, the duplications in the G gene seem to confer an evolutionary advantage.

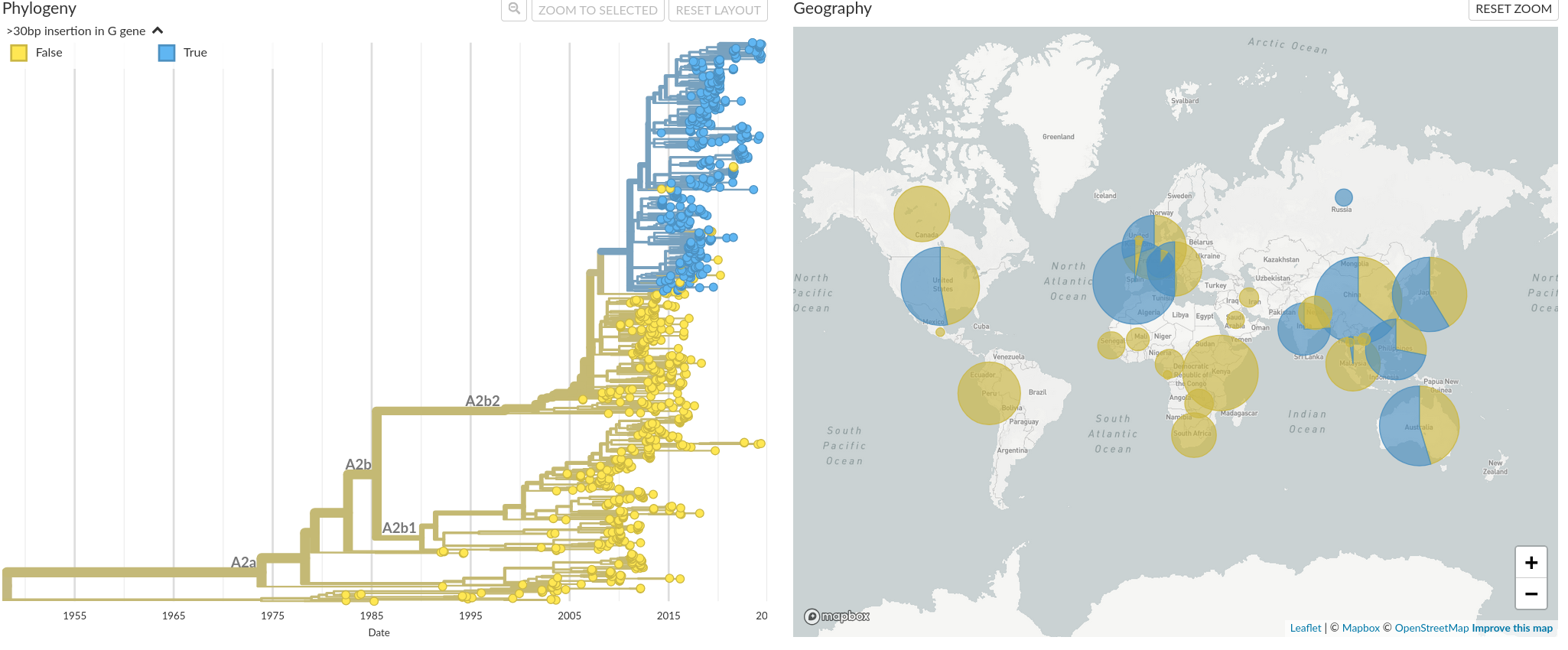

Figure 4. Time resolved phylogeny of clade A based on G gene sequences with blue coloring of G gene duplications. In our analysis of hMPV, it is possible to color the phylogenetic tree by the duplications in gene G. In continents for which recent data is available, like Asia, Australia, the US and Europe, we have seen an increasing prevalence of strains with duplications in the G gene.

Figure 4. Time resolved phylogeny of clade A based on G gene sequences with blue coloring of G gene duplications. In our analysis of hMPV, it is possible to color the phylogenetic tree by the duplications in gene G. In continents for which recent data is available, like Asia, Australia, the US and Europe, we have seen an increasing prevalence of strains with duplications in the G gene.

It will be interesting to observe how the emergence of these duplications will affect the spread and prevalence of different subclades. With sequencing tools becoming more widespread and with an increase in interest in sequencing respiratory viruses, we will hopefully be able to include more viral genomes in our analyses in the future, rendering Nextstrain a useful resource for tracking the real-time evolution of hMPV.

This work is made possible by the open sharing of genetic data by research groups from all over the world. We gratefully acknowledge their contributions.